By Georgia Silvera Seamans

How did Japanese ornamental cherry trees become part of the canopy of New York City?

In this blog post I follow ornamental cherries from the early 20th century gift of 300 trees to New York and the more famous gift to Washington DC. I then discuss cherry phenology, cherry trees in my favorite city park, Washington Square, and end with a shout out to the Black Cherry.

300 Cherry Trees for Henry Hudson’s “Discovery”

On August 27, 1909, the New York Times published a letter to the editor signed by a person who simply went by G. W. F. who wrote about the “Significance of the proposed gift from the Mikado.” (Emperor Meiji reigned during that time.) The proposed gift was 300 cherry trees to mark every year since the Hudson River “has been known to the world.” To the European world, as the river is known by other names to Indigenous peoples. G. W. F. argued the gift was important because the cherry flower is the national flower of Japan, and also “a symbol of the very soul of the manhood of Japan.” Oh!

On November 30, 1910, the New York Times[1] carried a story by the Japanese Consul General and members of the Committee of Japanese Residents of New York that the actual number of trees was 2,100 calculated by multiplying the 300 year history of the Hudson River by the lucky number 7. Sadly, when the shipment of trees was inspected disease and infestations were discovered so the trees were destroyed. According to the article, the Royal Botanical Gardens immediately propagated replacement trees with the expected delivery date of 1912. These new trees were planted in Sakura and Riverside Parks.

Cherry Diplomacy

The presence of Japanese flowering trees in the U.S. landscapes began with Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore’s first trip to Japan in 1885. She went there to visit her brother and was struck by the beauty of the flowering trees. When she returned to the U.S., she began a campaign to plant cherry trees in Potomac Park, a new park at the time along the river in Washington DC. Scidmore recruited First Lady Helen Taft, who had also visited Japan, to her cause. Coincidentally, Dr. Jokichi Takamine was visiting New York’s Japanese consul general Kokichi Mizuno in DC and heard about the Scidmore-Taft plan. Between the four of them, a gift of 2,000 trees from Tokyo to DC was cemented.

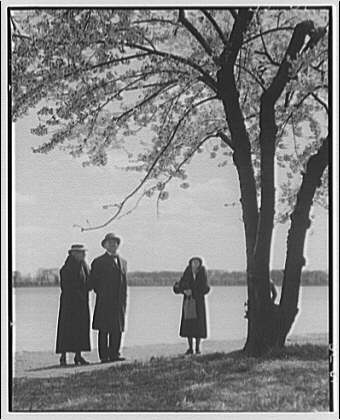

The cherry trees were shipped to DC via Seattle in 1910. An inspection on arrival revealed an infestation. The trees were destroyed. Then Tokyo Mayor Yukio Ozaki sent a replacement gift of 3,020 trees of 12 varieties. The Yoshino hybrid numbered 1,800. These cherries arrived free of pests and diseases in March 1912 and were summarily planted along the Tidal Basin and elsewhere in Potomac Park and the city. The National Park Service notes that less than 100 of the original 3,000 plus trees are alive today. Also, in partnership with the National Arboretum, cuttings from the survivor trees have been propagated and planted locally as well as being shared with the Japan Cherry Blossom Association in Japan.

Cherry Blossom Phenology

For the Washington Square Park Phenology Project, which launched in September 2019, I help to monitor three cherry trees (two Prunus serrulata ‘Kwanzan’ and one Prunus x yedoensis aka Yoshino) for the USA National Phenology Network Nature’s Notebook program. In 2024, Washington Square Park, representing NYC, was one of five locations in the International Cherry Blossom Prediction Competition. The average prediction for peak bloom for NYC was April 2nd. The peak bloom actually occurred on March 28th. The National Park Service defines peak bloom as 70% open flowers. The Japan Meteorological Corporation’s prediction for peak bloom in Kyoto was March 31st.

Flowering data has been recorded in Japan since the 9th century as part of the country’s hanami or annual cherry blossom festivals. From this 1200-year record, scientists Aono and Kazui (2008) extracted “a total of 732 records…from the 9th century to the present, or around 60% of the years, making this the longest and most complete record of phenology from any place in the world.”[2] Summarizing Aono’s and Kazui’s (2008) paper, Primack, Higuchi, and Miller-Rushing (2009) noted that “not only are cherries flowering earlier than at any time over the past 1200 years, but reconstructed temperatures indicate that they are experiencing warmer conditions than at any time during that period.”

I am writing from New York where the timing of flowering and leaf out have advanced in the state. Fuccillo Battle and colleagues (2022)—using two data sets: 1826-1872 and 2009-2017—found that “on average, plants flowered 10.5 days earlier and leaf 19 days earlier—with some species flowering up to 27 days earlier and leafing up to 31 days earlier over that time period.” The phenological response in urban areas, like New York City, is more pronounced. Flower gawkers should prepare to see blossoms earlier than in the past.

#FOMO

Usually media outlets don’t include Washington Square Park on their lists of places to see cherry blossoms in NYC. However, in a recent piece, the New York Times mentions “several Yoshino trees.” The park is also home to Kwanzan Cherries as mentioned before. My preference is for the Yoshino Cherry. The Yoshino flowers are visited by various bees. The cherry tree bears a delightfully bitter drupe. The Kwanzan Cherry is sterile; it is strictly ornamental, human eye candy. Speaking of which, traveling to parks to see the cherry blossoms is a big deal. People will step over protective fencing and trample ornamental bulbs to get their selfies or portraits taken. I have taken many photos of cherry flowers but I take care not to damage other plants while doing so.

Boost the Biodiversity Potential of Landscaped Parks

A few blocks from Washington Square (WSQ), a Black Cherry (Prunus serotina)—the bark looks like burned potato chips—grows in Time Landscape, a Land Art work by Alan Sonfist. I hope the Black Cherry will be the replacement species for the current ornamental cherries in WSQ. The Black Cherry accounts for 7.5% of the native midstory in the city’s forested natural areas. This native tree is the host plant for 10 moths and butterflies. We should maximize the host sites for native biodiversity throughout the city—let’s plant native species in landscaped parks.

[1] https://nyti.ms/3PSqnYr

[2] Primack, Richard B., Hiroyoshi Higuchi, and Abraham J. Miller-Rushing. “The impact of climate change on cherry trees and other species in Japan.” Biological Conservation 142.9 (2009): 1943-1949.